5. Other Conspiracy Arguments

In this section, I’ll respond to a few other common conspiracy arguments, which are not included in Jones’ or Sibrel’s lists.

In this section, I’ll respond to a few other common conspiracy arguments, which are not included in Jones’ or Sibrel’s lists.

5.1. “How could all the photos be perfect?”

A common CT argument is that all the photos taken on the Moon are of excellent quality, perfectly framed and perfectly exposed – the inference being that this “proves” that the photos were staged in a studio. The argument goes something like this: “The cameras were mounted on the front of the astronauts’ spacesuits, and had no finders – and the astronauts had to operate them while wearing bulky and awkward spacesuit gloves. How could they possibly have taken perfect pictures every time?”

A common CT argument is that all the photos taken on the Moon are of excellent quality, perfectly framed and perfectly exposed – the inference being that this “proves” that the photos were staged in a studio. The argument goes something like this: “The cameras were mounted on the front of the astronauts’ spacesuits, and had no finders – and the astronauts had to operate them while wearing bulky and awkward spacesuit gloves. How could they possibly have taken perfect pictures every time?”

The answer, of course, is that they

didn’t

! It’s just that only the best of the pictures have ever been published in the media, for obvious reasons.

The answer, of course, is that they

didn’t

! It’s just that only the best of the pictures have ever been published in the media, for obvious reasons.

Suppose you go on an exotic holiday, and like me, take hundreds of photos. Unless you’re a photographer of professional standard, your photos are not all likely to be perfect, are they? In my case, I usually end up with a whole range – a few are excellent, most ( hopefully ) are of acceptable quality, and a few are mediocre or downright rubbish. The latter are consigned to the bin, and only the better ones finish up in an album, to be shown to my family and friends. I’m sure the same applies to most people.

Suppose you go on an exotic holiday, and like me, take hundreds of photos. Unless you’re a photographer of professional standard, your photos are not all likely to be perfect, are they? In my case, I usually end up with a whole range – a few are excellent, most ( hopefully ) are of acceptable quality, and a few are mediocre or downright rubbish. The latter are consigned to the bin, and only the better ones finish up in an album, to be shown to my family and friends. I’m sure the same applies to most people.

Similarly, the thousands of photos taken during the Apollo missions included the whole range of good, bad and indifferent. But no-one

wants

to see the bad ones, do they? If an astronaut accidentally cut off the top of his colleague’s head, then that picture is never going to be printed in a book or glossy magazine, is it? Only the best few percent of the pictures have ever been published, because those are the ones which Joe Public wants to see. The remainder, once again, are

all

available in the NASA archives, to anyone who requests to see them.

Similarly, the thousands of photos taken during the Apollo missions included the whole range of good, bad and indifferent. But no-one

wants

to see the bad ones, do they? If an astronaut accidentally cut off the top of his colleague’s head, then that picture is never going to be printed in a book or glossy magazine, is it? Only the best few percent of the pictures have ever been published, because those are the ones which Joe Public wants to see. The remainder, once again, are

all

available in the NASA archives, to anyone who requests to see them.

Furthermore, everything that the astronauts did on the Moon was practiced over and over again on Earth – including the use of their cameras. NASA realised that the photos taken during the missions would form a valuable and important archive for posterity, so this part of the astronauts’ job was not taken lightly; they extensively practiced operating the cameras, to ensure that they

would

produce some good pictures.

Furthermore, everything that the astronauts did on the Moon was practiced over and over again on Earth – including the use of their cameras. NASA realised that the photos taken during the missions would form a valuable and important archive for posterity, so this part of the astronauts’ job was not taken lightly; they extensively practiced operating the cameras, to ensure that they

would

produce some good pictures.

As for the difficulty of operating the cameras while wearing spacesuit gloves; not surprisingly, the cameras were specially modified, with oversized knobs and levers, with this consideration in mind.

As for the difficulty of operating the cameras while wearing spacesuit gloves; not surprisingly, the cameras were specially modified, with oversized knobs and levers, with this consideration in mind.

5.2. “The photos are all perfect, but the TV pictures were fuzzy.”

This argument follows on from that discussed in Section 5.1. While

some

of the Apollo photos – those which we see published in books and magazines – are of excellent quality, the TV footage transmitted from the Moon during Apollo 11 was in very poor-quality, fuzzy and grainy black and white. According to the CTs, this is because the photos were carefully staged in the studio, to show only what NASA wanted us to see, while the TV pictures were deliberately

made

fuzzy and indistinct, so as to hide what was really happening.

This argument follows on from that discussed in Section 5.1. While

some

of the Apollo photos – those which we see published in books and magazines – are of excellent quality, the TV footage transmitted from the Moon during Apollo 11 was in very poor-quality, fuzzy and grainy black and white. According to the CTs, this is because the photos were carefully staged in the studio, to show only what NASA wanted us to see, while the TV pictures were deliberately

made

fuzzy and indistinct, so as to hide what was really happening.

Once again, they are talking utter drivel!

Once again, they are talking utter drivel!

First, the simple and obvious answer. In 1969, still photography was already a mature and quite sophisticated technology, the result of an entire century of research and development – no pun intended! Television, by comparison, was in its infancy. Only a little more than a decade earlier, the average household TV set had consisted of a huge four-foot-wide cabinet, with a tiny nine-inch screen in the middle, which had to be viewed through a magnifier. By 1969, colour TV had been around for just a few years, and was still an expensive luxury; the majority of households still possessed only a black and white set. In fact, some low-budget programmes were still being produced in black and white.

First, the simple and obvious answer. In 1969, still photography was already a mature and quite sophisticated technology, the result of an entire century of research and development – no pun intended! Television, by comparison, was in its infancy. Only a little more than a decade earlier, the average household TV set had consisted of a huge four-foot-wide cabinet, with a tiny nine-inch screen in the middle, which had to be viewed through a magnifier. By 1969, colour TV had been around for just a few years, and was still an expensive luxury; the majority of households still possessed only a black and white set. In fact, some low-budget programmes were still being produced in black and white.

Even for those programmes being made in colour, the picture quality was vastly inferior to that which we take for granted today. Today, if we watch programmes made in the 1960s or ‘70s – think of the re-runs of old classics, such as

Dad’s Army

, which are still shown from time to time – we can see that the picture quality is pretty abysmal, in comparison with present-day programmes. So it’s obvious that the Apollo footage appears of equally poor quality, by modern-day standards.

Even for those programmes being made in colour, the picture quality was vastly inferior to that which we take for granted today. Today, if we watch programmes made in the 1960s or ‘70s – think of the re-runs of old classics, such as

Dad’s Army

, which are still shown from time to time – we can see that the picture quality is pretty abysmal, in comparison with present-day programmes. So it’s obvious that the Apollo footage appears of equally poor quality, by modern-day standards.

However, there is rather more to this matter, which is not quite so obvious.

However, there is rather more to this matter, which is not quite so obvious.

Firstly, the CTs often appear to be judging everything in terms of what happened on Apollo 11, and seem to forget that five more Moon landing missions followed it! The poor, fuzzy, black and white TV pictures applied

only

to Apollo 11; on all the subsequent missions, the coverage was in colour, and of considerably better quality.

Firstly, the CTs often appear to be judging everything in terms of what happened on Apollo 11, and seem to forget that five more Moon landing missions followed it! The poor, fuzzy, black and white TV pictures applied

only

to Apollo 11; on all the subsequent missions, the coverage was in colour, and of considerably better quality.

So if, as the CTs claim, the Apollo 11 pictures were deliberately blurred to disguise what was really going on, then

why

would NASA have then shown us everything in far greater clarity on the later missions? That doesn’t make any sense, does it?

So if, as the CTs claim, the Apollo 11 pictures were deliberately blurred to disguise what was really going on, then

why

would NASA have then shown us everything in far greater clarity on the later missions? That doesn’t make any sense, does it?

Why there was such a difference between Apollo 11 and the later missions takes a little explaining. First, it should be pretty obvious that a colour TV picture contains more data than a black and white one – roughly three times as much, since for each “dot” in a black and white picture, a colour picture contains three dots, one for each of the three primary colours. Therefore, transmitting a colour picture, at the same rate of frames per second, requires data to be transmitted at three times the rate as for black and white.

Why there was such a difference between Apollo 11 and the later missions takes a little explaining. First, it should be pretty obvious that a colour TV picture contains more data than a black and white one – roughly three times as much, since for each “dot” in a black and white picture, a colour picture contains three dots, one for each of the three primary colours. Therefore, transmitting a colour picture, at the same rate of frames per second, requires data to be transmitted at three times the rate as for black and white.

What may not be so obvious to the layman is that transmitting data by radio at a higher rate requires a bigger antenna. Think of the Galileo probe, which was severely restricted in its ability to transmit data back from Jupiter, because its big high-gain dish antenna failed to unfurl properly. It had to make do with transmitting at a much lower data rate, through its smaller low-gain antenna, which vastly reduced the amount of data it was able to return.

What may not be so obvious to the layman is that transmitting data by radio at a higher rate requires a bigger antenna. Think of the Galileo probe, which was severely restricted in its ability to transmit data back from Jupiter, because its big high-gain dish antenna failed to unfurl properly. It had to make do with transmitting at a much lower data rate, through its smaller low-gain antenna, which vastly reduced the amount of data it was able to return.

To transmit a colour TV signal from the Moon to Earth, at the S-Band frequencies used by Apollo, requires a dish antenna at least 1.2 metres across. All of the missions, including Apollo 11, were able to transmit colour TV from the CM, since the main antenna mounted on the SM was more than adequate for this purpose. The LM, however, had only a small low-gain antenna, about 40 cm across; note its size in Fig. 4 ( in Section 2.1 ). This was capable of transmitting a low-grade black and white TV signal, but useless for colour.

To transmit a colour TV signal from the Moon to Earth, at the S-Band frequencies used by Apollo, requires a dish antenna at least 1.2 metres across. All of the missions, including Apollo 11, were able to transmit colour TV from the CM, since the main antenna mounted on the SM was more than adequate for this purpose. The LM, however, had only a small low-gain antenna, about 40 cm across; note its size in Fig. 4 ( in Section 2.1 ). This was capable of transmitting a low-grade black and white TV signal, but useless for colour.

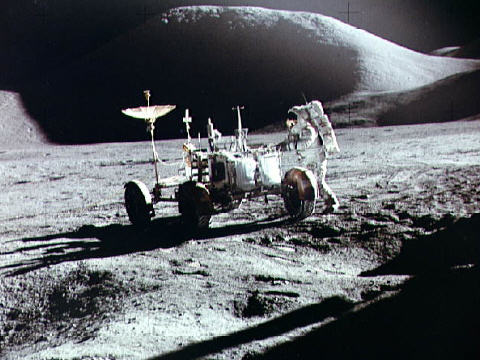

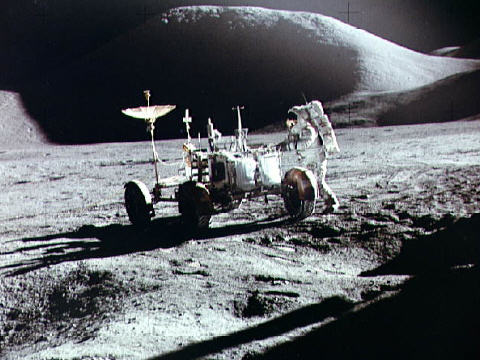

All the missions after Apollo 11 were able to transmit colour TV from the Moon, by means of a large, umbrella-like high-gain antenna, about 1.2 metres in diameter, which was erected on the lunar surface by the astronauts. On Apollos 12 and 14, this was free-standing; on Apollos 15-17, it was mounted on the Lunar Rover, as shown in Fig. 9. Actually, the Apollo 12 crew accidentally damaged their camera, and therefore were not able to transmit any TV pictures ( see Section 6.2 ).

All the missions after Apollo 11 were able to transmit colour TV from the Moon, by means of a large, umbrella-like high-gain antenna, about 1.2 metres in diameter, which was erected on the lunar surface by the astronauts. On Apollos 12 and 14, this was free-standing; on Apollos 15-17, it was mounted on the Lunar Rover, as shown in Fig. 9. Actually, the Apollo 12 crew accidentally damaged their camera, and therefore were not able to transmit any TV pictures ( see Section 6.2 ).

Fig. 9

So why didn’t Apollo 11 use a high-gain antenna on the Moon? There are two reasons. Firstly, Apollo 11 was a “bare minimum” mission; its purpose was simply to land two astronauts on the Moon and return them safely to Earth – in order to prove that it could be done, and fulfil Kennedy’s challenge of doing it before the end of the decade. Its LM stayed on the Moon for only a few hours, and Armstrong and Aldrin performed only a single 2½-hour moonwalk. So the mission planners didn’t want them to waste valuable time setting up a fancy antenna, merely so that the viewers on Earth could see prettier pictures; such luxuries would have to wait until the later missions. Apollo 11 would have to make do with what could be transmitted through the LM’s low-gain antenna. In fact, at the time of Apollo 11, the equipment needed to send colour TV on the later missions was still under development.

So why didn’t Apollo 11 use a high-gain antenna on the Moon? There are two reasons. Firstly, Apollo 11 was a “bare minimum” mission; its purpose was simply to land two astronauts on the Moon and return them safely to Earth – in order to prove that it could be done, and fulfil Kennedy’s challenge of doing it before the end of the decade. Its LM stayed on the Moon for only a few hours, and Armstrong and Aldrin performed only a single 2½-hour moonwalk. So the mission planners didn’t want them to waste valuable time setting up a fancy antenna, merely so that the viewers on Earth could see prettier pictures; such luxuries would have to wait until the later missions. Apollo 11 would have to make do with what could be transmitted through the LM’s low-gain antenna. In fact, at the time of Apollo 11, the equipment needed to send colour TV on the later missions was still under development.

Secondly, it was obvious that Armstrong’s first step onto the lunar surface would be a momentous and historic event; naturally, NASA wanted to record the moment for posterity. This was done by means of a remotely controlled TV camera, mounted on the outside of the LM. But obviously, this could

only

be transmitted through the low-gain antenna, as the astronauts couldn’t possibly deploy a high-gain antenna

before

they had descended onto the surface! So if those pictures could be transmitted using the low-gain antenna, then they could settle for sending

all

of the pictures that way.

Secondly, it was obvious that Armstrong’s first step onto the lunar surface would be a momentous and historic event; naturally, NASA wanted to record the moment for posterity. This was done by means of a remotely controlled TV camera, mounted on the outside of the LM. But obviously, this could

only

be transmitted through the low-gain antenna, as the astronauts couldn’t possibly deploy a high-gain antenna

before

they had descended onto the surface! So if those pictures could be transmitted using the low-gain antenna, then they could settle for sending

all

of the pictures that way.

There is one other aspect of the TV transmissions, about which some CTs have made a big deal. There was no direct feed of the Apollo 11 TV transmissions to broadcasting companies; the pictures were displayed only on a large TV screen in Mission Control, and the TV companies had to film the mission from this. Inevitably, CTs claim that this was to prevent the film being examined too closely.

There is one other aspect of the TV transmissions, about which some CTs have made a big deal. There was no direct feed of the Apollo 11 TV transmissions to broadcasting companies; the pictures were displayed only on a large TV screen in Mission Control, and the TV companies had to film the mission from this. Inevitably, CTs claim that this was to prevent the film being examined too closely.

But again, this applied only to Apollo 11; on the other missions, the transmissions

were

fed directly to the TV companies, after being sent from the Moon by a high-gain antenna. The reason for this was quite simple. The LM’s small low-gain antenna was not even capable of transmitting a black and white TV signal in standard television format; in order to use this antenna, the signal had to be “compressed”, by reducing the number of lines in the image and the number of frames per second. This reduced the required data transmission rate to only 5% of that required for colour TV. Naturally, it also degraded the quality of the TV pictures; this is another reason for the “fuzzy and grainy” appearance of the Apollo 11 footage.

But again, this applied only to Apollo 11; on the other missions, the transmissions

were

fed directly to the TV companies, after being sent from the Moon by a high-gain antenna. The reason for this was quite simple. The LM’s small low-gain antenna was not even capable of transmitting a black and white TV signal in standard television format; in order to use this antenna, the signal had to be “compressed”, by reducing the number of lines in the image and the number of frames per second. This reduced the required data transmission rate to only 5% of that required for colour TV. Naturally, it also degraded the quality of the TV pictures; this is another reason for the “fuzzy and grainy” appearance of the Apollo 11 footage.

To feed the transmissions directly to the TV networks would have required elaborate equipment to convert the compressed signal back into standard TV format. There was no point in developing this technology specially, just for one mission, so a low-tech solution was used instead. The pictures were displayed on the large screen in Mission Control, and the TV companies then filmed the scene from that screen, using their standard cameras.

To feed the transmissions directly to the TV networks would have required elaborate equipment to convert the compressed signal back into standard TV format. There was no point in developing this technology specially, just for one mission, so a low-tech solution was used instead. The pictures were displayed on the large screen in Mission Control, and the TV companies then filmed the scene from that screen, using their standard cameras.

Some may find it hard to believe that one of the most important events of the Twentieth Century was recorded for posterity by means of such crudely improvised equipment and techniques. But I’ll repeat the vital point; the primary purpose of Apollo 11 was simply to land two men on the Moon and return them safely. It was little more than an engineering test, to prove that it could be done. It had to be done within a tight timescale, to fulfil Kennedy’s “before the end of the decade” challenge – not to mention the requirement to beat the Russians to it!

Some may find it hard to believe that one of the most important events of the Twentieth Century was recorded for posterity by means of such crudely improvised equipment and techniques. But I’ll repeat the vital point; the primary purpose of Apollo 11 was simply to land two men on the Moon and return them safely. It was little more than an engineering test, to prove that it could be done. It had to be done within a tight timescale, to fulfil Kennedy’s “before the end of the decade” challenge – not to mention the requirement to beat the Russians to it!

Everything which the astronauts

did

on the Moon – sending TV pictures, setting up experiments and collecting rock samples – was added to the programme by NASA. On Apollo 11, these activities were kept to an absolute minimum and given lower priority; there would be plenty of time for them on the later missions. Indeed, some of the more sophisticated equipment, to be used on the later missions, was still under development.

Everything which the astronauts

did

on the Moon – sending TV pictures, setting up experiments and collecting rock samples – was added to the programme by NASA. On Apollo 11, these activities were kept to an absolute minimum and given lower priority; there would be plenty of time for them on the later missions. Indeed, some of the more sophisticated equipment, to be used on the later missions, was still under development.

All of this is explained in much greater technical detail on Jay Windley’s web site,

www.clavius.org

.

All of this is explained in much greater technical detail on Jay Windley’s web site,

www.clavius.org

.

5.3. “Who took the pictures?”

This has to be one of the most pathetic of all CT arguments! There are some lunar surface video sequences which show two astronauts together. The CTs claim that a third person must have shot the pictures; as only two men landed on the Moon on each mission, this “proves” that it was faked in a studio.

This has to be one of the most pathetic of all CT arguments! There are some lunar surface video sequences which show two astronauts together. The CTs claim that a third person must have shot the pictures; as only two men landed on the Moon on each mission, this “proves” that it was faked in a studio.

There is also, of course, the famous film showing Neil Armstrong descending the LM ladder and taking his historic first step onto the Moon. This was shot from below, looking upwards, while his colleague Buzz Aldrin was still inside the LM. According to the CTs, the film must have been shot by a cameraman lying on the ground.

There is also, of course, the famous film showing Neil Armstrong descending the LM ladder and taking his historic first step onto the Moon. This was shot from below, looking upwards, while his colleague Buzz Aldrin was still inside the LM. According to the CTs, the film must have been shot by a cameraman lying on the ground.

Once again, I would expect my ten-year-old nephew to be able to answer this…

Once again, I would expect my ten-year-old nephew to be able to answer this…

Now let’s see… In August 1999, I and three colleagues from Cleveland and Darlington Astronomical Society travelled to Bulgaria to observe a total solar eclipse. On the day of the eclipse, we drove in a hired car to our chosen observing site, and spent the day in a field in the middle of nowhere, a couple of miles from the nearest village. There were just the four of us there, without another human being within sight. Yet in my photo album, there is a photo of the four of us, posing together with our equipment. So who took

that

picture? The answer is the obvious one; I did – using a camera on a tripod with a self-timer mechanism.

Now let’s see… In August 1999, I and three colleagues from Cleveland and Darlington Astronomical Society travelled to Bulgaria to observe a total solar eclipse. On the day of the eclipse, we drove in a hired car to our chosen observing site, and spent the day in a field in the middle of nowhere, a couple of miles from the nearest village. There were just the four of us there, without another human being within sight. Yet in my photo album, there is a photo of the four of us, posing together with our equipment. So who took

that

picture? The answer is the obvious one; I did – using a camera on a tripod with a self-timer mechanism.

Similarly, in June 2004, my colleague Don Martin and I were in Turkey, observing the transit of Venus. Again, I have photos in my album which show the two of us at our observing site, with our equipment. This time, there

were

other people around, as we observed from the poolside at our hotel. But wait! Included in the photo is

my camera

, mounted on a tripod with a long lens, which I was using to photograph the transit! So who could possibly have taken

that

picture? Again, I did. There’s no law that says I can’t take more than one camera on a trip, is there? I used a second camera, with a self-timer, on a G-cramp mount attached to the back of a chair.

Similarly, in June 2004, my colleague Don Martin and I were in Turkey, observing the transit of Venus. Again, I have photos in my album which show the two of us at our observing site, with our equipment. This time, there

were

other people around, as we observed from the poolside at our hotel. But wait! Included in the photo is

my camera

, mounted on a tripod with a long lens, which I was using to photograph the transit! So who could possibly have taken

that

picture? Again, I did. There’s no law that says I can’t take more than one camera on a trip, is there? I used a second camera, with a self-timer, on a G-cramp mount attached to the back of a chair.

The point I’m making here is that the explanation for the “both astronauts” footage is trivial; doesn’t it occur to the idiots that it’s possible to operate a camera remotely? Obviously, Armstrong’s first step onto the Moon was a momentous and historic moment, and it would have been unthinkable not to record it for posterity! So a remotely-operated camera was mounted on the outside of the LM, specifically for the purpose. The camera was part of an equipment package called the Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly ( MESA ), which was strapped to the side of the LM descent stage, and was lowered like a drawbridge once the astronauts were on the Moon. As Armstrong began to descend the ladder, he pulled a lanyard which released a latch on the MESA, and the camera sprang outwards on a strut, into a position where it was aimed at the ladder. This procedure was clearly explained in a press pack which NASA issued to journalists before the event.

The point I’m making here is that the explanation for the “both astronauts” footage is trivial; doesn’t it occur to the idiots that it’s possible to operate a camera remotely? Obviously, Armstrong’s first step onto the Moon was a momentous and historic moment, and it would have been unthinkable not to record it for posterity! So a remotely-operated camera was mounted on the outside of the LM, specifically for the purpose. The camera was part of an equipment package called the Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly ( MESA ), which was strapped to the side of the LM descent stage, and was lowered like a drawbridge once the astronauts were on the Moon. As Armstrong began to descend the ladder, he pulled a lanyard which released a latch on the MESA, and the camera sprang outwards on a strut, into a position where it was aimed at the ladder. This procedure was clearly explained in a press pack which NASA issued to journalists before the event.

After both astronauts were on the surface, and the MESA had been lowered and opened, the camera was removed from it, and mounted on a tripod to film the rest of their activities.

After both astronauts were on the surface, and the MESA had been lowered and opened, the camera was removed from it, and mounted on a tripod to film the rest of their activities.

The later missions also used tripod-mounted TV cameras; Apollos 15-17 also had a camera mounted on the Lunar Rover, to film the EVAs at a distance from the LM.

The later missions also used tripod-mounted TV cameras; Apollos 15-17 also had a camera mounted on the Lunar Rover, to film the EVAs at a distance from the LM.

We also have yet another piece of selective thinking here. In 1965, Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov was filmed making his historic first spacewalk during the Voskhod 2 flight – while his colleague was inside the capsule and on the other side of a sealed hatch. The CTs apparently don’t doubt that

that

was done by a remotely-operated camera.

We also have yet another piece of selective thinking here. In 1965, Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov was filmed making his historic first spacewalk during the Voskhod 2 flight – while his colleague was inside the capsule and on the other side of a sealed hatch. The CTs apparently don’t doubt that

that

was done by a remotely-operated camera.

5.4. “The colour television signal from later missions was supposed to be ‘live’, but in fact NASA had equipment on the ground that would delay the signal before passing it on to news agencies.”

Yes, NASA

did

have such equipment – but it was not actually used on Apollo. It had, however, been used during the Mercury and Gemini programmes. NASA management feared that any “verbal indiscretion” by an astronaut could be a significant public relations embarrassment, so their voice transmissions were relayed to the media “not quite live” – with a delay of a few seconds in the circuit, enabling ground controllers to “bleep out” any inappropriate language. This was the

only

form of “censorship” which has

ever

been employed by NASA!

Yes, NASA

did

have such equipment – but it was not actually used on Apollo. It had, however, been used during the Mercury and Gemini programmes. NASA management feared that any “verbal indiscretion” by an astronaut could be a significant public relations embarrassment, so their voice transmissions were relayed to the media “not quite live” – with a delay of a few seconds in the circuit, enabling ground controllers to “bleep out” any inappropriate language. This was the

only

form of “censorship” which has

ever

been employed by NASA!

After the Apollo 1 tragedy, it was decided that being completely open and candid with the public was more important than protecting little old ladies who might be upset by naughty words, and the delay policy was dropped.

After the Apollo 1 tragedy, it was decided that being completely open and candid with the public was more important than protecting little old ladies who might be upset by naughty words, and the delay policy was dropped.

Proof that the Apollo transmissions were indeed truly “live” was provided during Apollo 16, with an incident of the very kind which the earlier delays had been intended to prevent. During a rest period in the LM, Commander John Young accidentally left his microphone switched on during a “private” conversation with his crewmate Charlie Duke, and treated the world’s viewers to an explicit description of the digestive problem which he was suffering, and a heartfelt complaint about the special diet to which the NASA doctors had subjected them. This was in the days when the use of a certain four-letter word on TV was still regarded as almost the end of civilisation as we knew it; Young’s use of that word on air left no possible doubt that we were hearing his words live and uncensored! ( He was most embarrassed, when his colleague on the ground interrupted him to tell him that he was going out to the world. )

Proof that the Apollo transmissions were indeed truly “live” was provided during Apollo 16, with an incident of the very kind which the earlier delays had been intended to prevent. During a rest period in the LM, Commander John Young accidentally left his microphone switched on during a “private” conversation with his crewmate Charlie Duke, and treated the world’s viewers to an explicit description of the digestive problem which he was suffering, and a heartfelt complaint about the special diet to which the NASA doctors had subjected them. This was in the days when the use of a certain four-letter word on TV was still regarded as almost the end of civilisation as we knew it; Young’s use of that word on air left no possible doubt that we were hearing his words live and uncensored! ( He was most embarrassed, when his colleague on the ground interrupted him to tell him that he was going out to the world. )

Gene Cernan also involuntarily let out a burst of “inappropriate” language, during a scary moment on Apollo 10 ( see Section 6.2 ).

Gene Cernan also involuntarily let out a burst of “inappropriate” language, during a scary moment on Apollo 10 ( see Section 6.2 ).

There was, in fact, a slight delay in the feed of “live” video signals to the TV stations. This was simply due to the requirement to convert the signal from one format to another. Standard format TV cameras, at that time, were too bulky and heavy to carry aboard a spacecraft, so special lightweight ones had been designed for Apollo. Instead of using three separate image sensor tubes for red, green and blue, as in a normal camera, the Apollo cameras used only a single tube, with a rotating colour filter wheel; in effect, the red, green and blue images for each frame were recorded “in series”, rather than “in parallel”, and were then combined into a colour image by equipment on the ground. This reduced both the weight of the cameras and the bandwidth required to transmit the signal – but the downside was that the pictures couldn’t be directly fed to TV stations; there was a brief unavoidable delay, while the signal was converted into standard TV format.

There was, in fact, a slight delay in the feed of “live” video signals to the TV stations. This was simply due to the requirement to convert the signal from one format to another. Standard format TV cameras, at that time, were too bulky and heavy to carry aboard a spacecraft, so special lightweight ones had been designed for Apollo. Instead of using three separate image sensor tubes for red, green and blue, as in a normal camera, the Apollo cameras used only a single tube, with a rotating colour filter wheel; in effect, the red, green and blue images for each frame were recorded “in series”, rather than “in parallel”, and were then combined into a colour image by equipment on the ground. This reduced both the weight of the cameras and the bandwidth required to transmit the signal – but the downside was that the pictures couldn’t be directly fed to TV stations; there was a brief unavoidable delay, while the signal was converted into standard TV format.

Again, for the technical details of how this system worked, see

www.clavius.org

.

Again, for the technical details of how this system worked, see

www.clavius.org

.

5.5. “The hatch of the Lunar Module wasn’t big enough for an astronaut, wearing a bulky spacesuit and backpack, to get through it.”

I heard this one from a gentleman whom I recently met, who buys into the conspiracy theory.

I heard this one from a gentleman whom I recently met, who buys into the conspiracy theory.

Certainly, the hatch wasn’t very big, and getting through it in a spacesuit was pretty awkward – but then, no-one ever said it was easy!

Certainly, the hatch wasn’t very big, and getting through it in a spacesuit was pretty awkward – but then, no-one ever said it was easy!

Using this as a conspiracy argument is ridiculous and pointless, for the following reasons. Firstly, if NASA had invested billions of dollars in such a vast and elaborate fake, does anyone actually imagine that they would have made such a stupid mistake? Secondly, the dimensions of the hatch are clearly stated in numerous books on Apollo and the history of spaceflight; I found references in two books on my own shelves, within five minutes. Had such a mistake been made, can anyone believe that not one of all those authors would have realised it? And finally, even if the landings had been faked, it would still have been necessary to make the hatch big enough, so the stand-in astronauts or actors could be filmed emerging from it!

Using this as a conspiracy argument is ridiculous and pointless, for the following reasons. Firstly, if NASA had invested billions of dollars in such a vast and elaborate fake, does anyone actually imagine that they would have made such a stupid mistake? Secondly, the dimensions of the hatch are clearly stated in numerous books on Apollo and the history of spaceflight; I found references in two books on my own shelves, within five minutes. Had such a mistake been made, can anyone believe that not one of all those authors would have realised it? And finally, even if the landings had been faked, it would still have been necessary to make the hatch big enough, so the stand-in astronauts or actors could be filmed emerging from it!

But for the record, let’s look at the facts. The LM ascent stage, which housed two astronauts, had two hatches. The first was the docking hatch, located at the top of the cabin, through which they entered the LM from the CM, to begin the descent to the Moon. This was circular, and 32 inches in diameter – which was quite adequate, as they didn’t need to go through it in full spacesuits. They entered the LM in their flight suits, and didn’t don their much bulkier EVA spacesuits and backpacks until after they had landed on the lunar surface.

But for the record, let’s look at the facts. The LM ascent stage, which housed two astronauts, had two hatches. The first was the docking hatch, located at the top of the cabin, through which they entered the LM from the CM, to begin the descent to the Moon. This was circular, and 32 inches in diameter – which was quite adequate, as they didn’t need to go through it in full spacesuits. They entered the LM in their flight suits, and didn’t don their much bulkier EVA spacesuits and backpacks until after they had landed on the lunar surface.

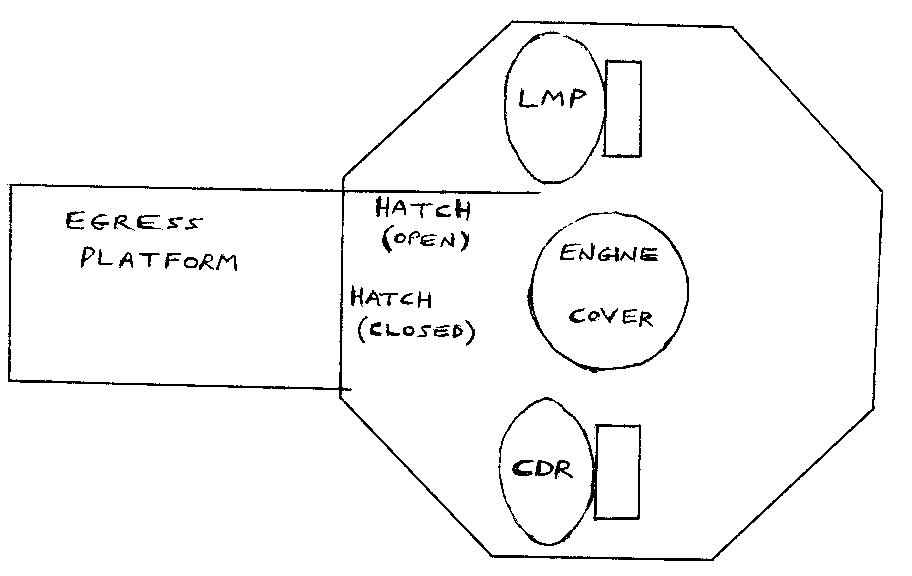

The second hatch was the forward hatch, through which they left the LM to perform their EVAs on the Moon. Outside it was a “porch”, or “egress platform” in NASA jargon, positioned on the flat top of the descent stage, which gave access to a ladder attached to one of the landing legs. ( See Fig. 4 in Section 2.1. ) This hatch was square, and 32 inches on a side – which was big enough for an astronaut to get through it in full spacesuit and backpack, but only just. In fact, they had to crawl through it on their stomachs – and when leaving the LM, they had to do so backwards! Each man crawled out feet first onto the egress platform ( Fig. 10 ), then stood up with the aid of handrails, ready to climb down the ladder. This was quite strenuous; in fact, the highest heart rates recorded among the astronauts occurred during this manoeuvre.

The second hatch was the forward hatch, through which they left the LM to perform their EVAs on the Moon. Outside it was a “porch”, or “egress platform” in NASA jargon, positioned on the flat top of the descent stage, which gave access to a ladder attached to one of the landing legs. ( See Fig. 4 in Section 2.1. ) This hatch was square, and 32 inches on a side – which was big enough for an astronaut to get through it in full spacesuit and backpack, but only just. In fact, they had to crawl through it on their stomachs – and when leaving the LM, they had to do so backwards! Each man crawled out feet first onto the egress platform ( Fig. 10 ), then stood up with the aid of handrails, ready to climb down the ladder. This was quite strenuous; in fact, the highest heart rates recorded among the astronauts occurred during this manoeuvre.

Fig. 10

The hatch was made so small, simply because there was no room to make it any bigger! In fact, it gave the designers of the LM significant headaches, figuring out how to make the hatch big enough for the astronauts to get through it, while ensuring that it didn’t obstruct the cramped interior of the cabin when it was opened. ( For obvious reasons, it had to open inwards. When the spacecraft was pressurised, the hatch had air on the inside and vacuum on the outside, so the positive pressure on the inside forced it shut against its gasket, helping to maintain the seal. The deck hatches on a submarine open outwards, for the equivalent and opposite reason. )

The hatch was made so small, simply because there was no room to make it any bigger! In fact, it gave the designers of the LM significant headaches, figuring out how to make the hatch big enough for the astronauts to get through it, while ensuring that it didn’t obstruct the cramped interior of the cabin when it was opened. ( For obvious reasons, it had to open inwards. When the spacecraft was pressurised, the hatch had air on the inside and vacuum on the outside, so the positive pressure on the inside forced it shut against its gasket, helping to maintain the seal. The deck hatches on a submarine open outwards, for the equivalent and opposite reason. )

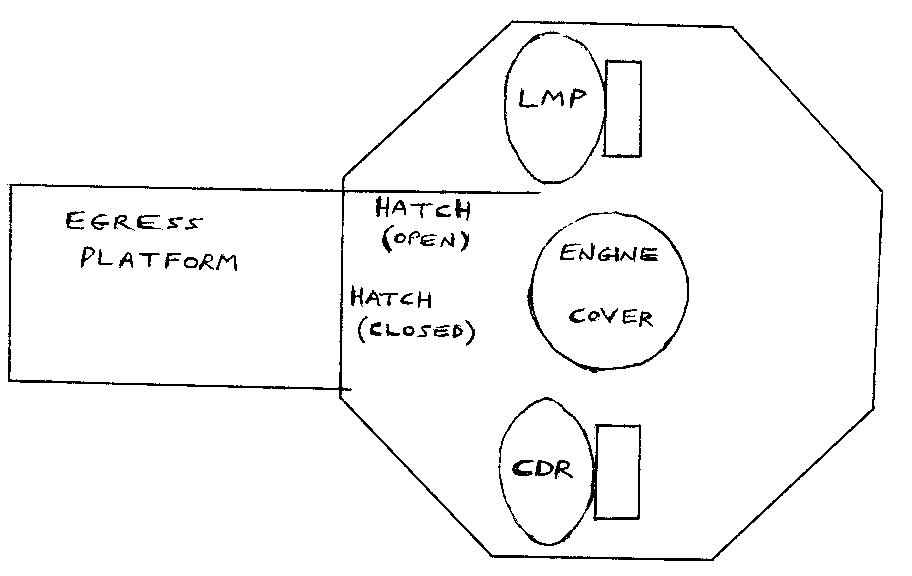

Fig. 11 shows a plan view of the ascent stage cabin; the interior was a mere 7.8 feet across. ( Its shape was an irregular polygon, but I’ve drawn it as an octagon for simplicity. ) In the centre was the cylindrical cover of the stage’s engine, which protruded up from the floor, and which was about two feet across.

Fig. 11 shows a plan view of the ascent stage cabin; the interior was a mere 7.8 feet across. ( Its shape was an irregular polygon, but I’ve drawn it as an octagon for simplicity. ) In the centre was the cylindrical cover of the stage’s engine, which protruded up from the floor, and which was about two feet across.

The position of the hatch, when open, is shown to scale. As can be seen, there was no room to make it any bigger, or the engine cover would have prevented it opening. Its height was also restricted by the design of the spacecraft, which required downward-tilted windows in front of the astronauts’ positions.

The position of the hatch, when open, is shown to scale. As can be seen, there was no room to make it any bigger, or the engine cover would have prevented it opening. Its height was also restricted by the design of the spacecraft, which required downward-tilted windows in front of the astronauts’ positions.

Fig. 11

On every lunar EVA, the Commander left the LM first, and re-entered it last. This was not simply a matter of protocol, but was dictated by the design of the LM. During flight, the Commander stood on the left, and the Lunar Module Pilot on the right, as shown in Fig. 11 ( the front of the cabin is to the left in the diagram ). After landing, when they had released their restraints, there was very little room to move around; once they were fully suited up and ready to begin an EVA, it was impossible for them to pass each other within the cabin and change places.

On every lunar EVA, the Commander left the LM first, and re-entered it last. This was not simply a matter of protocol, but was dictated by the design of the LM. During flight, the Commander stood on the left, and the Lunar Module Pilot on the right, as shown in Fig. 11 ( the front of the cabin is to the left in the diagram ). After landing, when they had released their restraints, there was very little room to move around; once they were fully suited up and ready to begin an EVA, it was impossible for them to pass each other within the cabin and change places.

The forward hatch was hinged on the LMP’s side; as can be seen in Fig. 11, when the hatch was opened, the hatch itself blocked his access to the opening. After the Commander had gone through the hatch, the LMP had to close it, move across into the Commander’s vacated position and open it again, before he could get down onto his belly and crawl out. The reverse applied on re-entering the LM. So it was, in fact, a physical impossibility for the LMP to go out first, or go back in last.

The forward hatch was hinged on the LMP’s side; as can be seen in Fig. 11, when the hatch was opened, the hatch itself blocked his access to the opening. After the Commander had gone through the hatch, the LMP had to close it, move across into the Commander’s vacated position and open it again, before he could get down onto his belly and crawl out. The reverse applied on re-entering the LM. So it was, in fact, a physical impossibility for the LMP to go out first, or go back in last.

5.6. “Gus Grissom’s Lemon”

Some CTs maintain that the Apollo programme was already in serious trouble, before the Apollo 1 tragedy of 27 January 1967. To back up this claim, they take a real incident and distort it to fit their own purpose. Astronaut Gus Grissom, a veteran of both Mercury and Gemini flights, was the Commander of the Apollo 1 crew, who were killed in the fire. Bart Sibrel, in his video A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Moon, claims that shortly before the tragedy, Grissom hung a lemon from the hatch of the Command Module in which he was due to fly, to indicate his dissatisfaction with the spacecraft. ( In American slang, an unreliable used car, or anything else regarded as useless, is referred to as “a lemon”. ) This is meant to prove that the astronauts themselves had no faith in the programme, even at that early stage.

Some CTs maintain that the Apollo programme was already in serious trouble, before the Apollo 1 tragedy of 27 January 1967. To back up this claim, they take a real incident and distort it to fit their own purpose. Astronaut Gus Grissom, a veteran of both Mercury and Gemini flights, was the Commander of the Apollo 1 crew, who were killed in the fire. Bart Sibrel, in his video A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Moon, claims that shortly before the tragedy, Grissom hung a lemon from the hatch of the Command Module in which he was due to fly, to indicate his dissatisfaction with the spacecraft. ( In American slang, an unreliable used car, or anything else regarded as useless, is referred to as “a lemon”. ) This is meant to prove that the astronauts themselves had no faith in the programme, even at that early stage.

Wrong! Grissom did no such thing. As a former military test pilot, he would not have taken what he considered unnecessary risks; had he

really

lacked confidence in the spacecraft, then he would probably have refused to fly in it!

Wrong! Grissom did no such thing. As a former military test pilot, he would not have taken what he considered unnecessary risks; had he

really

lacked confidence in the spacecraft, then he would probably have refused to fly in it!

What actually happened is well known in NASA circles, and has been related in at least one book ( details can be found on Jim McDade’s web site ); Grissom did, in fact, hang a lemon on a

simulator

.

What actually happened is well known in NASA circles, and has been related in at least one book ( details can be found on Jim McDade’s web site ); Grissom did, in fact, hang a lemon on a

simulator

.

There were two simulators, used to train the astronauts in handling the spacecraft, which mimicked the behaviour of the Apollo CSM in response to the controls. One of these was at Cape Canaveral, the other at Houston. They were built by North American Rockwell, the company which also built the CSM itself.

There were two simulators, used to train the astronauts in handling the spacecraft, which mimicked the behaviour of the Apollo CSM in response to the controls. One of these was at Cape Canaveral, the other at Houston. They were built by North American Rockwell, the company which also built the CSM itself.

As always happens with complex software systems, the software used to drive the simulators was updated many times, as bugs were identified and fixed. There were also a number of hardware upgrades. But Rockwell were not able to keep the updates synchronised between the two simulators, with the result that they ran different versions of the software, and sometimes behaved differently during identical flight simulations. Grissom, frustrated by these inconsistencies, hung a lemon on the Cape simulator as an expression of his feelings. He was dissatisfied with the simulators, not with the spacecraft itself.

As always happens with complex software systems, the software used to drive the simulators was updated many times, as bugs were identified and fixed. There were also a number of hardware upgrades. But Rockwell were not able to keep the updates synchronised between the two simulators, with the result that they ran different versions of the software, and sometimes behaved differently during identical flight simulations. Grissom, frustrated by these inconsistencies, hung a lemon on the Cape simulator as an expression of his feelings. He was dissatisfied with the simulators, not with the spacecraft itself.

Neither he nor anyone else ever hung a lemon on a CM, or

any

piece of actual Apollo hardware. This is yet another example of a CT making a sensationalist claim, without bothering to check the true facts.

Neither he nor anyone else ever hung a lemon on a CM, or

any

piece of actual Apollo hardware. This is yet another example of a CT making a sensationalist claim, without bothering to check the true facts.

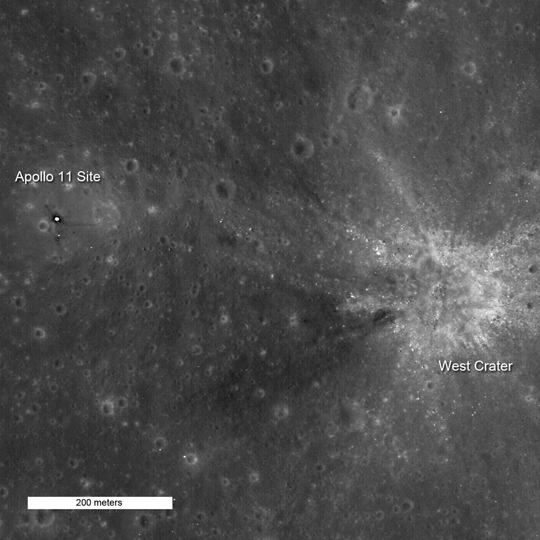

5.7. “Apollo 11 landed embarrassingly off target, four miles from its intended landing site, yet Apollo 12 managed to make a pinpoint landing, only 200 yards from Surveyor 3.”

The inference here is that it’s impossible to believe that such a huge improvement in accuracy could be achieved between the first landing and the second. The simple answer is – it wasn’t, nor did it need to be.

The inference here is that it’s impossible to believe that such a huge improvement in accuracy could be achieved between the first landing and the second. The simple answer is – it wasn’t, nor did it need to be.

This is yet another example of a CT distorting the real facts to suit his purpose. The second part of that statement is true, but the first is completely false.

This is yet another example of a CT distorting the real facts to suit his purpose. The second part of that statement is true, but the first is completely false.

First, let’s consider the second part. Surveyor 3, for the uninitiated, was one of a series of unmanned probes which NASA soft landed on the Moon in 1966-68, to study the properties of its surface in preparation for the Apollo landings. On Apollo 12, the plan was to land the Lunar Module close to Surveyor 3, which had landed in April 1967, so the crew could walk to it, and bring back parts of it for analysis, to determine the effect on materials of prolonged exposure to space. The goal was to land within 1000 yards of the probe; in fact, they achieved even better accuracy than that, and landed only about 200 yards from it.

First, let’s consider the second part. Surveyor 3, for the uninitiated, was one of a series of unmanned probes which NASA soft landed on the Moon in 1966-68, to study the properties of its surface in preparation for the Apollo landings. On Apollo 12, the plan was to land the Lunar Module close to Surveyor 3, which had landed in April 1967, so the crew could walk to it, and bring back parts of it for analysis, to determine the effect on materials of prolonged exposure to space. The goal was to land within 1000 yards of the probe; in fact, they achieved even better accuracy than that, and landed only about 200 yards from it.

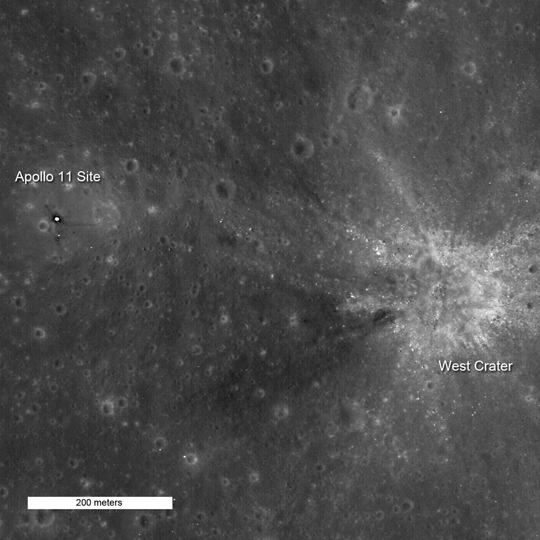

Now let’s consider the first part of the claim. Apollo 11’s landing was not “embarrassingly off target” at all! While the LM did indeed land four miles away from its intended target, there was nothing “embarrassing” or accidental about it; as is common knowledge, it was due to a deliberate change of plan by Neil Armstrong, in the interests of safety.

Now let’s consider the first part of the claim. Apollo 11’s landing was not “embarrassingly off target” at all! While the LM did indeed land four miles away from its intended target, there was nothing “embarrassing” or accidental about it; as is common knowledge, it was due to a deliberate change of plan by Neil Armstrong, in the interests of safety.

The LM’s descent was, in fact, dead on target, just about as accurate as that of Apollo 12. But during the final approach, the astronauts saw that their intended landing zone was a lot rougher than had been thought from orbital photos, and strewn with boulders. Landing there would have been dangerous – so Armstrong made a command decision to override the pre-programmed guidance. He took over manual control, and deliberately overshot the landing zone, in search of a smoother area of ground on which to set down.

The LM’s descent was, in fact, dead on target, just about as accurate as that of Apollo 12. But during the final approach, the astronauts saw that their intended landing zone was a lot rougher than had been thought from orbital photos, and strewn with boulders. Landing there would have been dangerous – so Armstrong made a command decision to override the pre-programmed guidance. He took over manual control, and deliberately overshot the landing zone, in search of a smoother area of ground on which to set down.

The only thing which the above argument proves is that its author didn’t bother to do even the most elementary research. The story of Apollo 11’s landing, and Armstrong’s manual override, is told in detail in practically every book which has ever been written about Apollo!

The only thing which the above argument proves is that its author didn’t bother to do even the most elementary research. The story of Apollo 11’s landing, and Armstrong’s manual override, is told in detail in practically every book which has ever been written about Apollo!

5.8. “Why is there no communication delay?”

At the time of Apollo, every child from the age of about eight upwards knew that the Moon is 239000 miles from the Earth. ( In the UK in those days, we all learned the numbers in miles. ) And every child with any degree of interest in science learned that the speed of light is 186000 miles per second.

At the time of Apollo, every child from the age of about eight upwards knew that the Moon is 239000 miles from the Earth. ( In the UK in those days, we all learned the numbers in miles. ) And every child with any degree of interest in science learned that the speed of light is 186000 miles per second.

Therefore, it takes light – and radio waves, which travel at the same speed – about 1.3 seconds to travel from the Earth to the Moon or vice versa. So when an astronaut on the Moon was talking to Mission Control ( there was only one person on each shift who directly spoke to the astronauts ), the radio signal took 1.3 seconds to travel in each direction, which means that when one person finished speaking, there was always a delay of 2.6 seconds before he heard the other begin to speak.

Therefore, it takes light – and radio waves, which travel at the same speed – about 1.3 seconds to travel from the Earth to the Moon or vice versa. So when an astronaut on the Moon was talking to Mission Control ( there was only one person on each shift who directly spoke to the astronauts ), the radio signal took 1.3 seconds to travel in each direction, which means that when one person finished speaking, there was always a delay of 2.6 seconds before he heard the other begin to speak.

So every TV broadcast from the Moon inevitably included these long pauses in every conversation. It was unavoidable, obviously, but a bit irritating for viewers!

So every TV broadcast from the Moon inevitably included these long pauses in every conversation. It was unavoidable, obviously, but a bit irritating for viewers!

However, in many TV documentaries which show some of the footage from the lunar surface, the delays are missing! When one person speaks, the other replies instantly. Inevitably, some CTs claim that this “proves” that the astronauts were not on the Moon at all, and it was being faked on Earth.

However, in many TV documentaries which show some of the footage from the lunar surface, the delays are missing! When one person speaks, the other replies instantly. Inevitably, some CTs claim that this “proves” that the astronauts were not on the Moon at all, and it was being faked on Earth.

So do they really imagine that if it was faked, NASA would have made such a childish mistake? Do they not think they would have made 2.6 second pauses to simulate the radio delay?

So do they really imagine that if it was faked, NASA would have made such a childish mistake? Do they not think they would have made 2.6 second pauses to simulate the radio delay?

The explanation is of course piddlingly simple. In every live transmission, the delays were indeed there. But in clips which were shown later in news programmes, or used in documentaries at a later date, they were simply edited out, because they were irritating to viewers! It’s that simple!

The explanation is of course piddlingly simple. In every live transmission, the delays were indeed there. But in clips which were shown later in news programmes, or used in documentaries at a later date, they were simply edited out, because they were irritating to viewers! It’s that simple!

Furthermore, it’s very common practice in making documentaries – about spaceflight or anything else – to edit out parts of people’s spoken words which are not relevant, or not of any interest, in order to keep the narrative flowing. Apollo documentaries are no exception.

Furthermore, it’s very common practice in making documentaries – about spaceflight or anything else – to edit out parts of people’s spoken words which are not relevant, or not of any interest, in order to keep the narrative flowing. Apollo documentaries are no exception.

For example, it’s commonly believed that the first words spoken on the surface of the Moon were Neil Armstrong’s announcement, “Houston, Tranquillity Base here. The Eagle has landed.” This appears to be the case in the footage which has often been presented in documentaries. But they were not!

For example, it’s commonly believed that the first words spoken on the surface of the Moon were Neil Armstrong’s announcement, “Houston, Tranquillity Base here. The Eagle has landed.” This appears to be the case in the footage which has often been presented in documentaries. But they were not!

The actual first words spoken, at the moment of touchdown, were extremely mundane; Aldrin said, “Contact light”- meaning that a light had illuminated to indicate that one of the probes beneath the footpads had touched the ground. Three seconds later, as the LM settled on the surface, Armstrong said “Shutdown”, and Aldrin replied, “Okay. Engine stop.”

The actual first words spoken, at the moment of touchdown, were extremely mundane; Aldrin said, “Contact light”- meaning that a light had illuminated to indicate that one of the probes beneath the footpads had touched the ground. Three seconds later, as the LM settled on the surface, Armstrong said “Shutdown”, and Aldrin replied, “Okay. Engine stop.”

There followed several sentences of technical status reports, indicating that everything had been shut down as it should be. 17 seconds after Aldrin’s first statement, Capcom Charlie Duke – the single person in Mission Control who was talking directly to the crew – said, “We copy you down, Eagle.”

There followed several sentences of technical status reports, indicating that everything had been shut down as it should be. 17 seconds after Aldrin’s first statement, Capcom Charlie Duke – the single person in Mission Control who was talking directly to the crew – said, “We copy you down, Eagle.”

Armstrong gave one last report, “Engine arm is off”, and then spoke those famous words. That 17 seconds of technical jargon would be meaningless and boring to the average layperson viewer, so in documentaries, it’s usually edited out.

Armstrong gave one last report, “Engine arm is off”, and then spoke those famous words. That 17 seconds of technical jargon would be meaningless and boring to the average layperson viewer, so in documentaries, it’s usually edited out.

Armstrong’s use of the name “Tranquillity Base” came as a surprise to Mission Control, as he made it up on the spot. Duke replied with some more famous words: “Roger, Tranquillity. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

Armstrong’s use of the name “Tranquillity Base” came as a surprise to Mission Control, as he made it up on the spot. Duke replied with some more famous words: “Roger, Tranquillity. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

But in fact, as Duke was momentarily taken aback, he initially stumbled on his words, and mispronounced “Tranquillity”, then corrected himself. Again, this mistake is normally edited out, because who actually cares about someone momentarily getting a word wrong? ( Except when it results in something comical, such as a newsreader mispronouncing the name of a politician and accidentally saying a rude word – in which case it will be repeated in compilations of “bloopers” for years to come! )

But in fact, as Duke was momentarily taken aback, he initially stumbled on his words, and mispronounced “Tranquillity”, then corrected himself. Again, this mistake is normally edited out, because who actually cares about someone momentarily getting a word wrong? ( Except when it results in something comical, such as a newsreader mispronouncing the name of a politician and accidentally saying a rude word – in which case it will be repeated in compilations of “bloopers” for years to come! )

So given that spoken words are routinely edited out for narrative clarity, why is it the slightest bit surprising that the radio delays are also removed?

So given that spoken words are routinely edited out for narrative clarity, why is it the slightest bit surprising that the radio delays are also removed?

For anyone who may be interested, the full transcript of that first conversation on the lunar surface can be found here:

MOON HOAX: DEBUNKED!: 9.7 Why is there no delay in the Apollo communications?

.

For anyone who may be interested, the full transcript of that first conversation on the lunar surface can be found here:

MOON HOAX: DEBUNKED!: 9.7 Why is there no delay in the Apollo communications?

.

5.9. “How could the Saturn V blueprints have been lost?”

The simple answer is, they haven’t!

The simple answer is, they haven’t!

For reasons which are not entirely clear, there is a common misconception that all the engineering blueprints for the Saturn V rocket have somehow been “lost”.

For reasons which are not entirely clear, there is a common misconception that all the engineering blueprints for the Saturn V rocket have somehow been “lost”.

In 1996, one John Lewis claimed in a book that he had tried in vain to obtain copies of the blueprints: “My attempts to find them several years ago met with no success; the plans have evidently been ‘lost’. The fleet has been destroyed. The plans are gone.”

In 1996, one John Lewis claimed in a book that he had tried in vain to obtain copies of the blueprints: “My attempts to find them several years ago met with no success; the plans have evidently been ‘lost’. The fleet has been destroyed. The plans are gone.”

The following year, James Collier, one of the authors responsible for popularising the conspiracy lunacy, similarly claimed that he had requested the blueprints of the Lunar Module from Grumman, the company which built it, and had been told that all the paperwork had been destroyed.

The following year, James Collier, one of the authors responsible for popularising the conspiracy lunacy, similarly claimed that he had requested the blueprints of the Lunar Module from Grumman, the company which built it, and had been told that all the paperwork had been destroyed.

Inevitably, some CTs claim that all the blueprints were not merely “lost”, but deliberately destroyed, to prevent any future researchers discovering that – according to them – the rocket and spacecraft didn’t actually work, and could never have gone to the Moon!

Inevitably, some CTs claim that all the blueprints were not merely “lost”, but deliberately destroyed, to prevent any future researchers discovering that – according to them – the rocket and spacecraft didn’t actually work, and could never have gone to the Moon!

Their claim that the rockets “didn’t work” is especially baffling! So what was it that actually lifted off on thirteen occasions, witnessed by millions? Even those CTs who claim that the spacecraft were only launched into low Earth orbit, or were launched without crews, can’t possibly deny that the rockets actually flew!

Their claim that the rockets “didn’t work” is especially baffling! So what was it that actually lifted off on thirteen occasions, witnessed by millions? Even those CTs who claim that the spacecraft were only launched into low Earth orbit, or were launched without crews, can’t possibly deny that the rockets actually flew!

16 Saturn V rockets were built, of which 13 were actually launched. The first two were used for unmanned tests of the Apollo spacecraft; the next ten launched the manned missions, Apollo 8 to 17. ( Apollo 7, the first manned test flight of the CSM in Earth orbit, was launched by a smaller Saturn 1B. ) The last one was used to launch the Skylab space station in 1973 – or rather, its first two stages were; the third stage was converted into the main hull of the station itself.

16 Saturn V rockets were built, of which 13 were actually launched. The first two were used for unmanned tests of the Apollo spacecraft; the next ten launched the manned missions, Apollo 8 to 17. ( Apollo 7, the first manned test flight of the CSM in Earth orbit, was launched by a smaller Saturn 1B. ) The last one was used to launch the Skylab space station in 1973 – or rather, its first two stages were; the third stage was converted into the main hull of the station itself.

Each of those launches of the manned missions was watched by tens of thousands of members of the public who were present in person ( at a safe distance of several miles! ), as well as by hundreds of millions of TV viewers worldwide.

Each of those launches of the manned missions was watched by tens of thousands of members of the public who were present in person ( at a safe distance of several miles! ), as well as by hundreds of millions of TV viewers worldwide.

The truth is that none of the blueprints have been “lost” or destroyed! In 2000, NASA confirmed that all Apollo blueprints are preserved on microfilm at Marshall Space Flight Centre in Huntsville, Alabama. More detail can be found here:

SPACE.com -- Saturn 5 Blueprints Safely in Storage

.

The truth is that none of the blueprints have been “lost” or destroyed! In 2000, NASA confirmed that all Apollo blueprints are preserved on microfilm at Marshall Space Flight Centre in Huntsville, Alabama. More detail can be found here:

SPACE.com -- Saturn 5 Blueprints Safely in Storage

.

Furthermore, the US Federal Archives in East Point, Georgia, stores a staggering 82 cubic metres of Apollo documents – that’s a huge amount of paper! – and Rocketdyne, the company which built the rocket’s engines, also preserves “dozens of volumes” of Saturn documents.

Furthermore, the US Federal Archives in East Point, Georgia, stores a staggering 82 cubic metres of Apollo documents – that’s a huge amount of paper! – and Rocketdyne, the company which built the rocket’s engines, also preserves “dozens of volumes” of Saturn documents.

Lewis’ claim that “the fleet has been destroyed” is also utter rubbish! The three Saturn Vs which were built, but never flew – they were built for the last three planned Apollo missions, which were subsequently cancelled – still exist, and are on public display for anyone to see! One is at Kennedy Space Centre in Florida, one at Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas, and the last at the US Space and Rocket Centre in Huntsville, Alabama. Each one is mounted horizontally and separated into its individual stages, for anyone to see close up. Here’s the one at KSC, photographed by me ( Fig. 12 ).

Lewis’ claim that “the fleet has been destroyed” is also utter rubbish! The three Saturn Vs which were built, but never flew – they were built for the last three planned Apollo missions, which were subsequently cancelled – still exist, and are on public display for anyone to see! One is at Kennedy Space Centre in Florida, one at Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas, and the last at the US Space and Rocket Centre in Huntsville, Alabama. Each one is mounted horizontally and separated into its individual stages, for anyone to see close up. Here’s the one at KSC, photographed by me ( Fig. 12 ).

Fig. 12

Of course, the only part of an Apollo spacecraft which returned to Earth was the Command Module. No less than twelve of the actual CMs which flew – all the manned ones, plus the unmanned Apollo 6 – are preserved in various museums, eleven in the US, and that of Apollo 10 in the London Science Museum. And three “spare” Lunar Modules – again, those which were built, but not used – are preserved at Kennedy Space Centre, the National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC and the Cradle of Aviation Museum in New York.

Of course, the only part of an Apollo spacecraft which returned to Earth was the Command Module. No less than twelve of the actual CMs which flew – all the manned ones, plus the unmanned Apollo 6 – are preserved in various museums, eleven in the US, and that of Apollo 10 in the London Science Museum. And three “spare” Lunar Modules – again, those which were built, but not used – are preserved at Kennedy Space Centre, the National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC and the Cradle of Aviation Museum in New York.

So any engineer wishing to learn about the technology of Apollo could learn a lot by examining close up all that still-existing hardware, as well as by studying the vast amount of documentation.

So any engineer wishing to learn about the technology of Apollo could learn a lot by examining close up all that still-existing hardware, as well as by studying the vast amount of documentation.

However, all of this does not mean it would be a simple matter to build a Saturn V or an Apollo spacecraft all over again today! Manufacturing, inspection and testing processes have changed beyond recognition since the 1960s; most of the machines and assembly lines used to build the rockets no longer exist, and most of the people with the skills to operate them are long dead! And thousands of components were used, which are no longer manufactured; in particular, it’s surely obvious that all the electronic components used have been obsolete for decades!

However, all of this does not mean it would be a simple matter to build a Saturn V or an Apollo spacecraft all over again today! Manufacturing, inspection and testing processes have changed beyond recognition since the 1960s; most of the machines and assembly lines used to build the rockets no longer exist, and most of the people with the skills to operate them are long dead! And thousands of components were used, which are no longer manufactured; in particular, it’s surely obvious that all the electronic components used have been obsolete for decades!

So to rebuild a Saturn V today would be incredibly difficult and expensive, as it would necessitate rebuilding the entire factories and production lines first. It’s far easier and cheaper to design and build a new rocket and spacecraft from scratch – which is of course exactly what NASA is doing!

So to rebuild a Saturn V today would be incredibly difficult and expensive, as it would necessitate rebuilding the entire factories and production lines first. It’s far easier and cheaper to design and build a new rocket and spacecraft from scratch – which is of course exactly what NASA is doing!

This is explained in more detail by Paolo Attivissimo in his excellent e-book, Moon Hoax: Debunked!:

MOON HOAX: DEBUNKED!: 9.6 How is it possible that the Saturn V blueprints have been lost?

. My thanks to Dave Evetts, for pointing me to this useful resource.

This is explained in more detail by Paolo Attivissimo in his excellent e-book, Moon Hoax: Debunked!:

MOON HOAX: DEBUNKED!: 9.6 How is it possible that the Saturn V blueprints have been lost?

. My thanks to Dave Evetts, for pointing me to this useful resource.

5.10. “Why didn’t the Russians even try to go to the Moon?”

This is one of the most baffling of all conspiracy arguments! Apparently, some conspiracy theorists believe that there never was a “race to the Moon”, and that the Soviet Union never even planned a manned lunar landing. Naturally, they conclude that the reason for this was that they realised at an early stage that it was impossible – perhaps due to the exaggerated radiation hazard of crossing the van Allen Belts, or all manner of other imaginary reasons – which therefore “proves” that the Americans couldn’t have done it either!

This is one of the most baffling of all conspiracy arguments! Apparently, some conspiracy theorists believe that there never was a “race to the Moon”, and that the Soviet Union never even planned a manned lunar landing. Naturally, they conclude that the reason for this was that they realised at an early stage that it was impossible – perhaps due to the exaggerated radiation hazard of crossing the van Allen Belts, or all manner of other imaginary reasons – which therefore “proves” that the Americans couldn’t have done it either!

But the race absolutely did happen! The Soviet Union certainly did have its own lunar landing programme, but cancelled it after they had lost the race, and then tried to save political face by denying that it had ever existed! However, it has been public knowledge since 1985!

But the race absolutely did happen! The Soviet Union certainly did have its own lunar landing programme, but cancelled it after they had lost the race, and then tried to save political face by denying that it had ever existed! However, it has been public knowledge since 1985!

To quote Paolo Attivissimo in Moon Hoax: Debunked!: “There actually was a Moon hoax, but not the one most space conspiracy theorists talk about: the Soviet one, meant to hide all evidence of their failed attempts to be the first to fly a crewed mission around the Moon and then achieve a crewed lunar landing.”

To quote Paolo Attivissimo in Moon Hoax: Debunked!: “There actually was a Moon hoax, but not the one most space conspiracy theorists talk about: the Soviet one, meant to hide all evidence of their failed attempts to be the first to fly a crewed mission around the Moon and then achieve a crewed lunar landing.”

The Soviet Union was in fact planning two different manned lunar missions. The first was to simply fly a manned spacecraft around the Moon and back to Earth ( on a free return trajectory, not to go into orbit as Apollo 8 did ). They initially hoped to do this before the US did.

The Soviet Union was in fact planning two different manned lunar missions. The first was to simply fly a manned spacecraft around the Moon and back to Earth ( on a free return trajectory, not to go into orbit as Apollo 8 did ). They initially hoped to do this before the US did.

Two different methods were considered to achieve this. One was to use a Proton rocket, which was then their biggest, with an added upper stage, to launch a Soyuz spacecraft directly to the Moon. The other involved launching two vehicles into Earth orbit with separate Protons, docking them and transferring crew between them, then one of them accelerating to the Moon.

Two different methods were considered to achieve this. One was to use a Proton rocket, which was then their biggest, with an added upper stage, to launch a Soyuz spacecraft directly to the Moon. The other involved launching two vehicles into Earth orbit with separate Protons, docking them and transferring crew between them, then one of them accelerating to the Moon.

But a number of events delayed the programme. The first was the sudden death of the Chief Designer, Sergei Korolev, in 1966, which threw the entire space programme into chaos, with a faction fight over who was to be his successor. Then came the tragedy of Soyuz 1; cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov was killed when his landing parachutes failed. This probably resulted from political pressure to fly the spacecraft before it was properly ready. Finally, there were problems with the reliability of the Proton rocket.

But a number of events delayed the programme. The first was the sudden death of the Chief Designer, Sergei Korolev, in 1966, which threw the entire space programme into chaos, with a faction fight over who was to be his successor. Then came the tragedy of Soyuz 1; cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov was killed when his landing parachutes failed. This probably resulted from political pressure to fly the spacecraft before it was properly ready. Finally, there were problems with the reliability of the Proton rocket.

In preparation for this, they sent four unmanned spacecraft on circumlunar flights, which carried a variety of small animals to study the effects on them of radiation exposure. The first of these, Zond 5, flew in September 1968, and it was widely believed that a manned mission would soon follow. In fact, NASA swapped the order of Apollos 8 and 9 in order to beat them to it!